DV And Intersectionality

By centering intersectionality, we can recognize the richness and complexity of people’s identities, beliefs, experiences, and the traditions, values, and relationships that serve as sources of meaning, strength, and resilience. We are also able to incorporate ways that survivors may identify justice and healing. Intersectionality requires individual and organizational reflection, collaboration, accountability, and intentional action.

Violence Free Colorado’s mission involves taking accountability for how historical events have laid the groundwork for present-day violence and oppression, comprehending the interconnectedness of various forms of oppression with domestic violence, dismantling systems and institutions that perpetuate violence and abuse, and cultivating alternative frameworks that nurture healthy relationships, communities, and societies.

How domestic violence overlaps with Additional forms of Oppression

Just as power and control are recognized as central to domestic violence (DV), they are at the core of additional forms of oppression like racism, ageism, ableism, homophobia, classism, and more. These are often referred to as “isms”. Moreover, DV and other oppressions are interconnected and need to always be addressed this way. To effectively combat DV, it’s imperative to acknowledge these intersections and collaborate with allied movements to address these interconnected challenges.

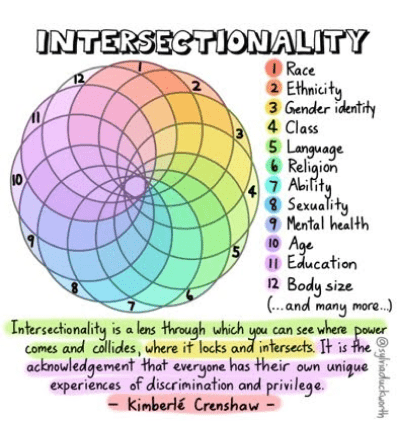

Kimberlé Crenshaw introduced the concept of intersectionality in 1989, defining it as:

“…a lens through which you can observe the convergence and interplay of power dynamics, recognizing where they intersect and intertwine. It acknowledges that each person has their own distinct experience of both discrimination and privilege.”

How domestic violence overlaps with Additional forms of Oppression

Without accountability for how power and control have been used in the past, we cannot shift the power dynamics that we are seeking to transform. Below are a few examples. However, they do not represent a complete story of historical and societal events of gender-based violence.

- Patriarchy laid the framework for the violence against women, femininity, and gender-diverse people. It also impacted the way our society perpetuates masculinity and its connection to power and control. This includes the denial of women’s voting rights, working rights, and full citizenship. Domestic violence and marital rape were not recognized as criminal acts and were normalized within the home.

- Prior to the colonization of what is now recognized as the United States, Indigenous communities were oftentimes matriarchal and did not experience gender and race-based violence. However, during colonization principles of violence such as ownership, superiority, and entitlement became entrenched in the Constitution, U.S. laws, and societal structures. White/European settlers believed in their entitlement to seize and occupy land already inhabited and nurtured by Indigenous peoples, resorting to attempted genocide with the goal of economic interests and power. The violence of the land was connected to violence against women.

- Similarly, racial hierarchies justified the ownership of people, using the institution of slavery, which directly impacted Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Pacific Islanders peoples.

- Gender non-conforming, nonbinary, and transgender identities were targeted with violence and attempted genocide.

The values of power and control justified violence on an ideological, individual, interpersonal, and institutional level1. These same concepts exist today and are still experienced by communities. It is important to recognize that unaddressed legacies of colonization, generational violence, and ongoing oppression undermine the creation of healing-centered and trauma-informed systems. There has been a lack of substantive changes to our social systems aimed at facilitating healing or proactively preventing occurrences of violence, abuse, and exploitation in the present and future.

Throughout the history of the United States, despite advancements such as the repeal of harmful laws, the expansion of rights, and the shifting of cultural norms away from violence and oppression, there has persistently existed a coordinated backlash rooted in racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, and similar biases2. Additionally, there is a contingent within the so-called “moderate middle” which undermines justice and liberation by prioritizing comfort and silence over the pursuit of justice. This backlash, along with complacency, is evident in contemporary society, manifesting in various forms such as the targeting of transgender youth, the erosion of reproductive rights, violence against Black Indigenous People Of Color (BIPOC) communities, removal of immigrant and refugee rights, instances of gun violence, the marginalization of disabled individuals, ongoing denial of Indigenous sovereignty, and more.

1 Refer to the Four I’s Of Oppression in Resources

2 Refer to Social Justice Definitions list in Resources

Oppression within The Anti-violence Movement

“So often the hierarchical and inequitable divides produced by global capitalism, imperialism, white supremacy, patriarchy, and heteronormativity get played out in our relationships and communication as well as in our organizations, activism and advocacy.”

Ann Russo, Feminist Accountability Disrupting Violence and Transforming Power

When it comes to causing harm, the anti-violence movement is no exception. There were/are many gaps in services for communities that experience overlapping intersectional barriers. Understanding how we got to where we are matters.

- Faced with a lack of structured support for survivors and widespread societal ideas about what domestic violence is, survivors rallied together to offer assistance to each other: providing safe housing, sharing resources and knowledge, and advocating for transformative change.

- As awareness increased and survivor support evolved into a more structured system, the anti-violence movement gradually shifted from its grassroots beginnings, towards a more institutionally driven approach. This inherently left our communities with overlapping experiences of individual and institutional oppression based on identities such as race, class, gender (specifically non-conforming), ability, etc. Survivors with these overlapping identities were pushed out of the movement and places of safety.

- 1950’s-60’s the Civil Rights era began to highlight the historical violence against Black communities and the demand for rights and freedom. This prompted collective consciousness of violence and oppression from many communities including Asian American, and Indigenous communities, who created the American Indian Movement (AIM) as well as influenced the Disability Justice Movement. The overlapping societal violence made it difficult for communities of color to highlight domestic violence in their communities without a widespread understanding of the different levels of experienced violence. Many of these communities were not even allowed in stores, or basic human rights at this point.

- Up until this point communities with disabilities were not centered in the anti-violence movement. The Disability Justice movement was influenced by the Civil Rights Movement and the fight against segregation and for inclusion in the law. Survivors in this community had very little support or understanding of barriers.

- During the 1970s and 80s, the mainstream (predominantly white-led) anti-violence movement embraced law enforcement and the criminal justice system as the primary means to address and eradicate domestic violence. Communities of Color, Disability Justice communities, and LGBTQ2S+ communities were advocating for a community response approach, which minimized further violence in their communities.

Without an understanding of intersectionality, we miss that the ongoing barriers created historically persist within current anti-violence efforts today. The power and control of history can show up in our policies and practices, hiring, retention, language access, limited mobility access, awareness of domestic violence in different cultural contexts, etc. Domestic violence is unique depending on people’s social location, identity, race, class, gender, ability, age, etc., and is highly influenced by the changing political society.

New ways of being and why it’s important

“Deconstructing historical discrimination enhances a cultural understanding of the development of certain systems of dehumanization, which offer [advocates] and [survivors] with a blueprint for reconnecting with humanity–an element that is foundational for healing”

Estrellado, Felipe & Celestial, Clinical Interventions for Internalized Oppression

The pursuit of anti-oppression is an ongoing, collective endeavor that requires daily commitment and accountability.

“A communal approach to accountability means that we build relationships and communities that can hold the inevitable conflict, oppression, and difficulty that we will inevitably experience given the ongoing work of interlocking systemic oppression.”

Ann Russo, Feminist Accountability Disrupting Violence and Transforming Power

While history presents numerous instances of what we should avoid; it also offers evidence of more just, equitable, and sustainable societal models that can flourish. An intersectional approach to advocacy is more holistic and survivor-centered. Alternative approaches to domestic violence, rooted in community empowerment and accountability, encompass a range of strategies: restorative justice initiatives, reduced reliance (or complete avoidance) of the criminal justice system in response to domestic violence, universal access to housing, establishment of mutual aid networks, and provision of non-punitive support for individuals seeking to address abusive behaviors and enact positive change.

Indeed, many of the “alternative” approaches to addressing and preventing violence, now gaining more recognition within the mainstream domestic violence movement, have their origins in BIPOC communities. It’s imperative to recognize, center, and heed the roots and leadership of these communities, as well as honor their lived experiences.

Here’s Our Stance

We are committed to always increasing our knowledge and learning. We invite and welcome feedback on ways we can better live up to these stances and support the work of allied justice movements.

We signed on to the Moment of Truth in 2020, and support the following stances it contains:

- Reframe the idea of “public safety” – to promote and utilize emerging community-based practices that resist abuse and oppression and encourage safety, support, and accountability.

- Provide safe housing for everyone – to increase affordable, quality housing, particularly for adult and youth survivors of violence, and in disenfranchised communities.

- Decriminalize survival – and address mandatory arrest, failure to protect, bail (fines and fees), and the criminalization of homelessness and street economies (sex work, drug trades, etc.).

- Remove police from schools – and support educational environments that are safe, equitable, and productive for all students.

- Please read our land acknowledgment (link).

- We embrace inclusion with Full Scholarships for Indigenous Centered Programs.

- We support Land Back Movement.

- We support MMIW (missing & murdered indigenous women) awareness.

- We support Indigenous Language preservation.

- We support Indigenous Food Soverting.

- We support Indigenous freedom of “Religious” Practices/Ceremony.

- We endorse policies aimed at securing funding and enhancing access to affordable housing for all residents of Colorado, inclusive of survivors and individuals grappling with abusive behaviors. Additionally, we advocate for policies enabling survivors to utilize sick days and job-protected leave to seek support in response to partner abuse.

- We advocate for domestic violence survivors to have access to no-barrier/low-barrier flexible financial assistance whenever needed, without limitations on duration. Achieving this goal necessitates a transition in funding practices from local to national levels. As part of our ongoing efforts, we actively engage funders to promote awareness of the importance of flexibility in funding allocation.

- We advocate for a transformation in community-based anti-domestic violence advocacy, moving away from temporary sheltering towards innovative service models that offer survivors immediate access to flexible financial assistance and support in securing safe and stable long-term housing. Accomplishing this transition entails a reorientation of funding priorities and increased flexibility from funding entities to enable domestic violence agencies to more effectively address the needs of survivors. Recognizing that this shift will require time, our technical assistance staff provides guidance and support to local domestic violence agencies and shelters in Colorado, aiding them in implementing harm reduction strategies and enhancing cultural responsiveness within their shelter services.

- We support policies and protocols that foster safer, more supportive, and more equitable environments for bilingual advocates.

- We create programing that is inclusive, accessible, and seeks to address historical trauma, oppression and disenfranchisement.

- We support policies that protect LGBTQ+ individuals’ right to marry.

- We provide training and technical assistance on supporting LGBTQ+ survivors in anti-violence advocacy and regularly bring in outside speakers on this topic as well.

- We support policies that protect all individuals’ rights and access to gender-affirming care and participation in sports/activities that align with their gender identity.

- We provide ongoing training and technical assistance on the barriers that immigrant survivors experience and how that overlaps with domestic violence services.

- We support policies that keep ICE officials out of public spaces, including courts and hospitals.

- We support culturally responsive services, protect DACA recipients, etc.

- No one is illegal.

- We support implementing an inclusive and comprehensive curriculum covering topics like sex education, healthy relationships, gender and sexuality, accurate history, and equity. Reforming disciplinary practices to abolish the school-to-prison pipeline. Addressing issues related to teacher pay and support. Addressing disparities in resources and opportunities between schools.

- We believe that education is social change and access is equity.

- We advocate for policies that allocate funding towards comprehensive sex education, which includes instruction on healthy relationships and violence prevention.

- We support that individuals should have the autonomy to make informed decisions regarding their reproductive health, including the choice of whether to become pregnant or remain pregnant.

- Violence Free Colorado upholds a pro-choice stance, endorsing policies that safeguard the right to access reproductive and sexual health care.

Our Stance

Violence Free Colorado holds systemic privileges and engages with established systems that have historically imposed obstacles for communities with intersecting identities.

As the state coalition, we are dedicated to fostering accountability in eradicating all manifestations of oppression and leveraging our privilege to educate our collaborators and non-Indigenous individuals with whom we interact.

References and Additional Resources

- Feminist Accountability Disrupting Violence and Transforming Power by Ann Russo

- Clinical Interventions for Internalized Oppression by Jan E. Estrellado, Lou S. Felipe, and Jeannie E. Celestial

- Building Identity and Solidarity: Asian American activism of the 1960s and ‘70s. A Library of Congress resource/user guide by Olivia Hewang

- ABC’s of Social Justice Definitions

- Bridges’ Social Justice Definitions

- PFLAG National Glossary